- Details

- Written by: Seán Ó Séaghdha

- Hits: 2710

Cuireadh an téacs thíos mar aguisín do Leabhar na Nornaightheadh Ccomhchoitchionn (Leabhar na nUrnaí Coitinne) a foilsíodh sa bhliain 1712. Leaganacha athchóirithe: PDF ePUB

Tabhair faoi deara gur leabhar eile ar fad atá in The Elements of the Irish Language, grammatically explained in English le Aodh Buí Mac Cruitín a foilsíodh sa bhliain 1728.

§ 1. Of the LETTERS.

The LETTERS are only theſe 18 following.

| Name. | Figure. | Pronunciation. | Name. | Figure. | Pronunciation. |

| Ailim | A a | a Lat. or Fr. | Luis | L l | l |

| Beith | B b | b | Muin | M m | m |

| Coll | C c | k | Nuin | N n | n |

| Duir | D d | d | Onn | O o | o |

| Eadh | E e | e Lat. or Fr. | Peithboc | P p | p |

| Fearn | F f | f | Ruis | R r | r |

| Gort | G g | g Gr. | Sail | S s | s |

| Uath | H h | h | Tinne | T t | t |

| I i | i Fr. or se Eng. | Uir | U u | u oo Eng. |

§. 2. Of Vowels, Dipthongs and Tripthongs.

THe Vowels are a, e, i, o, u. A, O, U, broad : E, I, ſmall. Of the various compoſitions of the Vowels, ariſe 13 Dipthongs, and 5 Tripthongs, according to this old Rule, in which their ſeveral Claſſes are diſtinguiſhed by Terms of Art, beginning with the leading Vowel of each Claſs, Viz.

Ceiṫre haṁarċ[ll ríoṁṫar ann,

Ć[g h>ḃaḋa fós go coitċ=nn,

Ć[g ifíne muin ar ṁ[n.

Trí huilleanna ; oir na haon8.

Of the firſt ſort called aṁarċ[ll, or Apthongs, i. e. Dipthongs or Tripthongs beginning with the Vowel a, there are four, of which three are Dipthongs, and one a Tripthong, as followeth,

| ae | } | Lae rae laeṫeaṁul. | ||

| ai | } | Fáiḋ, maiṫ, saiṫ, | long or ſhort. | |

| ao | } | ć{r ḿ{r s{r |

{ | This Dipthong is always long, and hath a peculiar ſound not uſed in any other Language that I know ; which may be learned by the Ear. |

| aoi | } | caoi. maoin. raoir | long. |

Of the ſecond ſort called Eaḃa, or Ephthongs, there are four Dipthongs, and one Tripthong.

| ea | Geal, s=l, séad, | long, or ſhort. |

| ei | Ceil, féil, meil, | long or ſhort. |

| eo | Céol, ceo, ceolan, | long. |

| ea | Céud, seud, meud, meur, | long. |

| eoi | Feoil, treoir, beoir, | long. |

Of the third ſort called ifíne, or Iphthongs, there are three Dipthongs, and two Tripthongs.

| ia | Srían, grían, mían, | long. |

| io | Fíor, iolar, iolarḋa, | long or ſhort. |

| iu | Fliuċ, tiuġ, diul, | long or ſhort. |

| iai | Diaiġ, a ndiaiġ a gcriaiḋ | long. |

| iui | Stiuir, an ċi[l, ci[n, | long. |

There is but one Ophthong called oir, o being prefixed to no Vowel but i, as coir, cóir, long or ſhort.

There are three Uill=nna, or Upthongs, whereof two are Dipthongs and one a Tripthong. viz.

| ua | Fuáṫ, sluaġ, tuaḋ, | long. |

| ui | Fuil, ś[l, ́[r, | long or ſhort. |

| uai | Búail, fuáir, uáir, | long. |

1. Note, That theſe Dipthongs ae, ao, eo, eu, ia, and all Tripthongs are long, and therefore need not be marked with an acute in Writing or print.

2. Note, That all Vowels coming together without a consonant interpoſing, make but one Syllable.

3. Note, That the Iriſh always put an accent over the Vowel, that is to be pronounced long, thus ( ´ ).

§. 3 Of the Conſonants.

The Conſonants when they are ſingle, have the ſame force in Iriſh, as in Engliſh : only c is always pronounced as k ; and s before e or i is pronounced as ſh ; but before a, o, u, it hath the ſame power with an Engliſh s.

When two c’s are joined together, they are pronounced as g ; thus, ccuid, is read guid. And two t’s have the force of d ; as tteaċ is read d=ċ. When d goes before n, it is pronounced as n ; thus c>d0na is céanna. Likewiſe, when d is placed before l, it hath the force of another l ; and ln are read as two lls, e. g. codlah , to Sleep, is read as collah ; and colna, of the Body, as colla.

ng, called Niatul in Iriſh, is for the moſt part pronounced as γγ in the Greek ; ſo aingeal, is pronounced as aγγeλ.

The Iriſh do not delight much in Conſonants, and therefore h is frequently added to b, c, d, f, g, m, p, s, t, to ſoſten the Language.

bh, and mh in the beginning and middle of words have the force of v Conſonant ; but in the latter end they, (and eſpecially mh) are pronounced a little flatter, when they come after a or e.

ch is read as the Greek χ.

dh and gh, ( which are often uſed indifferently for one another, ) have ſometimes in the beginning, and middle of a word, the force of y, and ſometimes they have a pronounciation, which is better learned by the Ear, than any deſcription that can be given of it. But always in the End, and commonly in the middle of a word, they are pronounced only as h.

sh and th are pronounced as h alone, thus shuil, is huil ; and thomas is homas.

The variation of a word in Number, Caſe, or Tenſe, is very often indicated by adding a different Conſonant to the Initial one ; and then the Initial Conſonant ( called litir ṡ=lḃuiġṫe, i. e. the poſſeſſive Letter, becauſe it poſſeſſes the firſt place in the Nominative Caſe, or preſent Tenſe indicative ) is quieſcent, and the additional only pronounced ; thus pobul in the Nominative, is altered into bpobul in the Ablative, the p not being pronounced , but the Initial or Poſſeſſive Letter is always written, to ſhew the Primative, or Radix of the word.

The greateſt difficulty of Reading, or ſpeaking Iriſh conſiſts in pronouncing dh, gh, and the Dipthongs and Tripthongs aright ; but this is readily attained by a little inſtruction by the Ear, and Practice ; whereby the Pronunciation of the Language is rendered eaſy and agreeable, there being much uſe made of Vowels, and little of Conſonants in it.

Iriſh Abbreviations uſed in this BOOK.

| ⁊ , | 8 , | ́{ : | @ : | = , | > . | 0n : | [ , | ́[ . | ḃ , | ċ , | ḋ , | ḟ , | ġ , | ṁ , | ṗ , | ṡ , | ṫ. |

| agus | air | ao : | chd : | ea , | éa : | nn : | ui | úi . | bh , | ch , | dh , | fh , | gh , | mh , | ph , | sh , | th. |

LONDON, Printed by Eleanor Everingham, at the Seven

Stars in Ave-Mary-Lane, A. D. 1712.

- Details

- Written by: Seán Ó Séaghdha

- Hits: 206

Rinne mé an léarscáil seo mar chabhair ar mo chuid taighde ginealais i gCo. Shligigh Theas. Is mór an cúnamh é beagán tuiscint a bheith agat ar tíreolaíoch áitiúil agus tú ag déanamh taighde den chineál seo! Níl a fhios agam an mbeadh sé fóinteach do dhuine eile, ach seo é. Fuair mé cuid mhaith den eolas ó townlands.ie agus openstreetmap.org. Is féidir le gach aon duine mapaí mar seo a chruthú ag uMap.

Rugadh mo mháthair ar An gCoill Ramhar sa bhliain 1917 agus ba é Nic Giolla Mhártain/Gilmartin a sloinne breithe.

I made this map as an aide in doing family research in southern Co. Sligo. It’s a great help to have a bit of an understaning of local geography when you’re doing this sort of research. I don’t know if it would be useful to anyone else, but here it is. I got a lot of this info from townlands.ie and openstreetmap.org. Anyone can create maps like this at uMap.

My mother was born in Coolrawer (Cloonraver) in 1917 and Gilmartin/Nic Giolla Mhártain was her maiden name.

- Details

- Written by: Seán Ó Séaghdha

- Hits: 5926

Westport 21 June 1802

Mr John McCracken

Dr Sir I posted a letter to you on fryday the 4th of June requiring an immediate answer giving account of my progreſs in Castlebarr &·c· and requested that you should remit me 4 or 5 guineas and to direct to the care of the Rev Doctor Lynagh in Westport. I have gotten no answer — I am uneasy — I suspect that my letter was suppreſsed or detained so that it had not come to yr hand — I hope the moneyis not lost. I know not what to think of it, or how to proceed. The Revd Dr Lynagh is a worthy gentleman, I have agreed with him that you shall write immediately to him and send the notes enclosed for me without having my name on the outside and they should be safe. But if you have received my letter, and have sent the notes, and that yr letter is detained from me — in that case I must leave it to yr own judgment how I shall be relieved out of this place — there is a Mr Datten a Merchant, in this town — perhaps you could find means to draw on him for a supply for me. Doctor Lynagh advises me to procure as soon as poſsible some credentials in form declaring the design of my Miſsion and this formula to be approved and signed by some well known Military gentleman such as General Drommond &c

I am sorry I had not such with me from the beginning — for tho the times are peaceable the people here are still suspicious of strangers and it is with difficulty I can convince them that I have no design in traveling but merely to procure Irish songs to be set to Music. I have had good succeſs till now, but the want of money impedes my progreſs. I send you here a list of 150 songs with the names of the persons and places where I got them for Mr Bunting’s use. I wd be glad he was here now — I wish you could let me know whether I may expect him or not

I am Sir with respect yrs

Patrick Lynch

- Details

- Written by: Seán Ó Séaghdha

- Hits: 16679

- Details

- Written by: Seán Ó Séaghdha

- Hits: 12225

The meaning and origin of the surname Ó Séaghdha has always been obscure, so when I spied a reference to Séaghdha in an index to Seathrún Céitinn’s 1634 Foras Feasa ar Éirinn (“Foundation of Knowledge on Ireland”), I was interested to see what he was up to. Drowning Vikings it seems.

By the way, the reign of Donnchadh mac Floinn tSionna AKA Donnchadh Donn mac Flainn was from 919 until his death in 944.

(Engrish below)

Liber secundus

XXII.

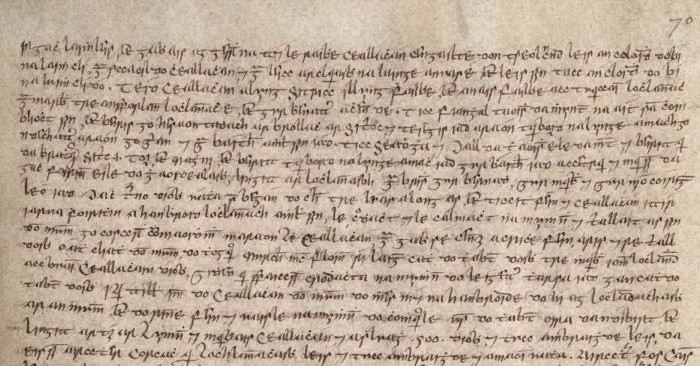

Is i ḃflaiṫeas Donnċaḋa mic Floinn tSionna rí Éireann do rinneaḋ na gníoṁa-so síos. Óir is i dtosaċ a ḟlaiṫis do ġaḃ Ceallaċán mac Buaḋaċáin ré ráiḋtear Ceallaċán Caisil ceannas dá ċóigeaḋ Muṁan ar feaḋ deiċ mbliaḋan. Féaċ mar ṫáinig Cinnéide mac Lorcáin go Gleannaṁain i gcoṁḋáil uaisle Muṁan sul do ríoġaḋ Ceallaċán agus do ṁeas Cinnéide teaċt idir Ċeallaċán is ríoġaċt Ṁuṁan. Giḋeaḋ táinig máṫair Ċeallaċán a Caiseal, óir is ann do ċoṁnuiġ rí i ḃfoċair a hoideaḋa coṁorba Pádraig, agus ar dteaċt san gcoṁḋáil di aduḃairt ré Cinnéide cuiṁniuġaḋ ar an dáil do ḃí idir Ḟiaċaiḋ Muilleaṫan is Ċormac Cas fá oiġreaċt Ṁuṁan do ḃeiṫ fá seaċ idir an dá ṡlioċt ṫiocfaḋ uaṫa leaṫ ar leaṫ; gonaḋ da ḟaisnéis sin atá an rann-so ar ḃriaṫraiḃ na mná:

Cuiṁniġ a Ċinnéide ċais,

Dáil Ḟiaċaċ is Ċormaic Cais,

Gur ḟágsad Muṁan do roinn

Go ceart idir a gcaoṁċloinn.

Agus táinig d’aiṫeasc na mná gur léig Cinnéide flaiṫeas Muṁan do Ċeallaċán.

Da éis sin do ġaḃadar Loċlannaiġ Ceallaċán i gceilg, gur ḃeanadar síol nEoġain is Dál gCais amaċ da n-aiṁḋeoin é. Iar mbriseaḋ iomorro iomad caṫ do Ċeallaċán is d’uaisliḃ Muiṁneaċ ar Loċlannaiḃ, agus iar n-a n-ionnarbaḋ as an Muṁain, is í coṁarle ar ar ċinn Sitric mac Tuirgéis fá hardtaoiseaċ orra cleaṁnas do luaḋ ré Ceallaċán, mar atá a ṡiúr féin Béiḃionn inġean Tuirgéis do ṫaḃairt mar ḃainċéile dó, agus saoirse dá Ċúigeaḋ Muṁan do ḃeiṫ aige ó Loċlonnaiḃ gan agra gan éiliuġaḋ ’n-a diaiḋ air, ionnus an tan do raċaḋ Ceallaċán ar a ionċaiḃ féin do ṗósaḋ a ṡeaṫraċ go muirḃfiḋe é féin is an ṁéid d’uaisliḃ Muiṁneaċ do ḃiaḋ mar aon ris; agus do léig cogar na ceilge sin le Donnċaḋ mac Floinn rí Teaṁraċ ar mbeiṫ i ḃfaltanas ré Ceallaċán dó tré gan cíos Muṁan do ḋíol ris, agus uime sin aontuiġis do Ṡitric an ċealg d’imirt ar Ċeallaċán is ar uaisliḃ Muiṁneaċ. Leis sin cuiris Sitric teaċta do luaḋ an ċleaṁnasa ré Ceallaċán agus ar roċtain do na teaċtaiḃ do laṫair Ċeallaċáin is eaḋ do ṫogair mórṡluaiġ do ṫaḃairt leis do ṗósaḋ na mná. “Ní haṁlaiḋ is cóir,” ar Cinnéide mac Lorcáin, “óir ní dleaġair an Ṁuṁa d’ḟágḃáil gan ċosnaṁ; agus is eaḋ is indéanta ḋuit neart sluaġ d’ḟágḃáil ag coiṁéad na Muṁan agus ċeiṫre fiċid mac tiġearna do ḃreiṫ leat do ṗósaḋ na mná.”

Agus is í sin coṁairle ar ar cinneaḋ leo; agus ar dtriall san turas soin do Ċeallaċán an oiḋċe sul ráinig go hÁṫ Cliaṫ, fiafruiġis Mór, inġean Aoḋa mic Eaċaċ inġean ríoġ Inse Fionnġall do ba bean do Ṡitric, créad fá raiḃe ag déanaṁ cleaṁnasa ré Ceallaċán i ndiaiḋ ar ṫuit d’uaisliḃ Loċlonnaċ leis? “Ní ar a leas luaiḋtear an cleaṁnas liom,” ar sé, “aċt ar tí ceilge d’imirt air.”

Beaḋgais an ḃean leis na briaṫraiḃ sin, ar mbeiṫ ḋi i ngráḋ folaiġṫeaċ ré Ceallaċán ré cian d’aimsir roiṁe sin, ón tráṫ do ċonnairc i bPort Lairge é, agus do-ní moiċéirġe ar maidin ar n-a ṁáraċ is téid ós íseal ar an raon ’n-a ṡaoil Ceallaċán do ḃeiṫ ag teaċt; agus mar ráinig Ceallaċán do láṫair beiris sise i ḃfód fá leiṫ é agus noċtais dó an ċealg do ḃí ar n-a hollṁuġaḋ ag Sitric ’n-a ċoṁair ré a ṁarḃaḋ; agus mar do ṁeas Ceallaċán tilleaḋ ní raiḃe sé ar cumas dó óir do ḃádar na maiġe ar gaċ leiṫ don ród lán do scoraiḃ Loċlonnaċ i n-oirċill ar a ġaḃáil. Mar do ṫogair tilleaḋ tar a ais luiġṫear leo-san da gaċ leiṫ air agus marḃṫar drong do na huaisliḃ do ḃí ’n-a ḟoċair, is marḃṫar leo-san mar an gcéadna luċt do na Loċlonnaiḃ. Giḋeaḋ lingid an-trom an tsluaiġ ar Ċeallaċán gur gaḃaḋ é féin is Donn Cuan mac Cinnédiḋ ann, is rugaḋ go hÁṫ Cliaṫ ar láiṁ iad, is ar sin go hArd Maċa mar a raḃadar naoi n-iarla do Loċlonnaiḃ go n-a mbuiḋin da gcoiṁéad.

Dála na druinge do ċuaiḋ as ón gcoinḃlíoċt soin d’uaisliḃ Muiṁneaċ, triallaid don Ṁuṁain is noċtaid a scéála do Ċinnéide agus leis sin ollṁuiġṫear dá ṡluaġ lé Cinnéide do ṫóraiḋeaċt Ċeallaċáin, mar atá sluaġ do ṫír is sluaġ do ṁuir; agus do rinne taoiseaċ ar an sluaġ do ḃí do ṫír do Ḋonnċaḋ mac Caoiṁ rí an dá Ḟearmaiġe, agus do ġaḃ Cinnéide ag cur ṁeisniġ ann aga ṁaoiḋeaṁ air go raḃadar aoinrí déag da ṡinnsearaiḃ i ḃflaiṫeas Muṁan, mar atá Airtre, Caṫal mac Fionġaine, Fionġaine mac Caṫail, Cú gan Ṁáṫair, Caṫal ré ráiḋtí Ceann Géagáin, Aoḋ, Flann Caṫraċ, Cairbre, Crioṁtann, Eoċaiḋ, is Aonġus mac Natfraoiċ. Do ċuir Cinnéide fós deiċ gcéad do Ḋál gCais leis is triúr taoiseaċ ós a gcionn, mar atá Coscraċ Longargán is Conġalaċ, aṁail adeir an laoiḋ: Éirġeaḋ fiċe céad buḋ ṫuaiḋ.

Ag so an rann as an laoiḋ ċéadna ag aiṫḟrioṫal briaṫar Ċinnédiḋ:

Éirġeaḋ ann Coscraċ na gcaṫ,

Agus Longargán laġaċ,

Éirġeaḋ Conġalaċ ón linn,

Mo ṫrí dearḃráiṫre aderirim.

Do ċuir Cinnéide fós cúig céad oile do Ḋál gCais lé Síoda ma Síoda ó ċloinn Ċoiléin ann, agus cúig céad oile do Ḋál gCais lé Deaġaiḋ mac Doṁnaill i n-éagmais a ndeaċaiḋ do ṡluaġ ó ṡaorċlannaiḃ oile Muṁan ann. Do ċuir an dara mórṡluaġ do ṁuir ann agus Failḃe Fionn rí Deasṁuṁan ’n-a ṫaoiseaċ orra.

Dála na sluaġ do ṫír, triallaid as an Muṁain i gConnaċtaiḃ is do léigeadar sceiṁiolta go Muaiḋ is go hIorrus is go hUṁall do ṫionól ċreaċ go foslongṗort Muiṁneaċ; agus ní cian do ḃádar an foslongṗort ag fuireaċ ris na sceiṁealtaiḃ an tan atċonncadar sluaġ deiġeagair ag teaċt da n-ionnsaiġe, agus fá hé a líon deiċ gcéad agus aonóglaoċ ’n-a réaṁṫosaċ; agus mar ráinig do láṫair riafruiġis Donnċaḋ mac Caoiṁ cia hiad an tsluaġḃuiḋean soin. “Dream do Ṁuiṁneaċaiḃ iad,” ar sé, “mar atáid Gaileanga is Luiġne do ċloinn Taiḋg mic Céin mic Oiliolla Óluim agus fir Ḋealḃna do ṡlioċt Dealḃaoiṫ mic Cais mic Conaill Eaċluaiṫ atá ag taḃairt neirt a laṁ liḃ-se tré ċommbáiḋ ḃráiṫreasa ré cur i n-aġaiḋ Ḋanar agus ré buain Ċeallaċáin ríoġ Muṁan díoḃ. Agus atáid trí taoisiġ áġṁara i gceannas an tsluaiġ-se, mar atá Aoḋ mac Dualġusa is Gaileanga uile uime, Diarmaid mac Fionnaċta is Luiġniġ uime, is Donnċaḋ mac Maoldoṁnaiġ ós fearaiḃ Dealḃna ann.” Agus is da ḋearḃaḋ sin atá an laoiḋ seanċusa darab tosaċ an céadrann-so:

Atfuilit sonn clanna Céin,

Agus Dealḃaoiṫ ar aoinréim,

Ag toiġeaċt is an sluaġaḋ,

Is buḋ liḃ-se a n-iommbualaḋ.

Agus is aṁlaiḋ do ḃádar an sluaġ-so .i. cúig céad díoḃ ’n-a luċt sciaṫ is cloiḋeaṁ agus cúig céad ’n-a saiġdeoiriḃ. Triallaid as sin i dTír Ċonaill an sluaġ Muiṁneaċ agus an ḟuireann soin táinig do ċongnaṁ leo mar aon, agus creaċtar an tír leo. Tig Muirċeartaċ mac an Arnalaiḋ d’iarraiḋ aisig na gcreaċ go háiseaċ ar Ḋonnċaḋ mac Caoiṁ; agus aduḃairt Donnċaḋ naċ tiuḃraḋ aċt fuiġeall sásuiġṫe na sluaġ ḋó don ċreiċ. Leis sin tréigis Muirċeartaċ an sluaġ agus cuiris teaċta ós íseal go cloinn Tuirgéis i nArd Maċa ’gá ḟaisnéis dóiḃ an sluaġ Muiṁneaċ do ḃeiṫ ag tóraiḋeaċt Ceallaċáin ar tí a ḃuana amaċ.

Dála ċloinne Tuirgéis triallaid a hArd Maċa naonḃar iarla go n-a sluaġ Loċlonnaċ, is Ceallaċán is Donn Cuan i mbroid leo. Iomṫúsa sluaġ Muṁan triallaid go hArd Maċa is marḃaid a dtarla da gcóir do Loċlonnaiḃ agus ar a ċlos ar n-a ṁáraċ ḋóiḃ Sitric go n-a ṡluaġ do ḋul ré Ceallaċán go Dún Dealgan triallaid ’n-a dtóraiḋeaċt, agus mar do ṁoṫuiṫ Sitric iad ag teaċt i ngar don ḃaile, téid féin is a ṡluaġ ’n-a longaiḃ is Ceallaċán is Donn Cuan leo, agus tig an sluaġ Muiṁneaċ ar imeall na tráġa ar a gcoṁair, agus iad ag agallṁa Loċlonnaċ. Agus leis sin atċíd caḃlaċ mór ag tiġeaċt san ċuan ċuca, agus tugadar Muiṁniġ aiṫne gurab é Failḃe Fionn go n-a ċaḃlaċ do ḃí ann.

Triallais Failḃe go n-a ċaḃlaċ go réimḋíreaċ i ndáil na Loċlonnaċ agus tug uċt ar an luing i n-a raiḃe Sitric is Tor is Maġnus, agus lingis ar bord luinge Ṡitreaca isteaċ agus dá ċloiḋeaṁ ’n-a ḋá láiṁ; agus gaḃais ag gearraḋ na dtéad lé raiḃe Ceallaċán ceangailte don tseolċrann, leis an gcloiḋeaṁ do ḃí ’n-a láiṁ ċlí, gur scaoil do Ċeallaċán is gur léig ar ċláraiḃ na luinge anuas é; agus leis sin tug cloiḋeaṁ na láiṁe clí do Ċeallaċán. Téid Ceallaċán a luing Ṡitreaca i luing Ḟailḃe agus anais Failḃe ag coṁṫuargain Loċlonnaċ gur marḃaḋ tré anḟorlann Loċlonnaċ é, is gur ḃeanadar a ċeann de. Tig Fianġal taoiseaċ da ṁuinntir ’n-a áit san ċoinḃlíoċt soin, is beiris go heasaontaċ ar ḃrollaċ ar Ṡitric, is teilgis iad ar aon tar bord na luinge amaċ, go ndeaċadar go grian, gur báṫaḋ aṁlaiḋ sin iad.

Tig Séaġḋa is Conall dá ṫaoiseaċ oile is beirid ar ḋá ḃráṫair Ṡitreaca, .i. Tor is Maġnus is beirid tar bord na luinge amaċ iad, gur báṫaḋ aṁlaiḋ sin iad a gceaṫrar. Agus mar sin da gaċ fuireann oile do Ġaeḋealaiḃ, lingid ar Loċlonnaiḃ, gur briseaḋ is gur bearnaḋ gur marḃaḋ is gur míoċóiriġeaḋ leo iad, go naċ téarna ḋíoḃ uaṫa aċt beagán do ċuaiḋ tré luas a long as, agus tigid féin is Ceallaċán i dtír ar n-a ḟóiriṫin a hanḃroid Loċlonnaċ aṁlaiḋ sin lé cróḋaċt is lé calmaċt na Muiṁneaċ; agus triallaid as sin don Ṁuṁain mar aon lé Ceallaċán, gur ġaḃ sé ceannas a ċríċe féin arís.

Agus ré dtriall dóiḃ ó Áṫ Cliaṫ don Ṁuṁain do ṫogair Murċaḋ mac Floinn rí Laiġean caṫ do ṫaḃairt dóiḃ tré ṁarḃaḋ Loċlonnaċ ag buain Ċeallaċáin díoḃ. Giḋeaḋ ar ḃfaicsin ċróḋaċta is ċalmaċta na Muiṁneaċ do léigeadar tarsa iad gan caṫ do ṫaḃairt dóiḃ.

⁜ Internet Archive: Foras Feasa ar Éirinn · The History of Ireland, Cumann na Sgíḃeann Gaeḋilge 1908, lch. 222

⁜ CELT: Foras Feasa ar Éirinn (Book I-II)

⁜ Meamram Páipéar Ríomhaire: UCD Franciscan Library MS A 14, f. 69 r. ar aghaidh

Liber secundus

XXII.

It was in the reign of Donnchadh son of Flann Sionna, king of Ireland, that the following events took place. For it was at the beginning of his reign that Ceallachán, son of Buadhachán, called Ceallachán of Cashel, held the sovereignty of the two provinces of Munster for ten years. Now Cinneide, son of Lorcán, came to Gleannamhain to an assembly of the nobles of Munster before Ceallachán was inaugurated, and Cinneide thought to come between Ceallachan and the kingship of Munster. But Ceallachán’s mother came from Cashel, since it was there she dwelt with her tutor, Patrick’s successor, and coming into the assembly she asked Cinneide to remember the agreement that was between Fiachaidh Muilleathan and Cormac Cas that the inheritance of Munster should alternate between their descendants, and this is expressed by this verse on the woman’s words:

Remember kind Cinnéide,

The agreement of Fiachach and Cormaic Cas,

How they left Munster shared

Justly amongst their noble children.

And as a result of the woman’s homily Cinnéide left the sovereignty of Muster to Ceallachán.

After this the Norsemen seized Ceallachán by treachery, but he was rescued by the síol Eoghain and the Dál gCais in spite of them. However, after Ceallachán and the nobles of Munster had defeated the Norsemen in many battles and driven them out of Munster, the strategy decided by Sitric, son of Turgesius, their leader, was to put forward a match with Ceallachán, that is to give his own sister Beibhionn, daughter of Turgesius, to him as wife, and allow him free possession of the provinces of Munster, without retribution or claim from the Norsemen on them; so that when Ceallachán went under his protection to marry his sister, he could be killed along with all the Munster nobles who were with him; and he gave word of this plot to Donnchadh, son of Flann, king of Tara, who had a grudge against Ceallachán for not paying the rent for Munster, and because of that he agreed to Sitric carrying out the plot against Ceallachán and the Munster nobles. Thereupon Sitric sent envoys to tell Ceallachán of the match and when they the envoys came to where Ceallachán was, he was inclined to take a large host with him to marry the woman. “That’s not right,” said Cinnéide, son or Lorcán, “for it would not be just to leave Munster undefended; and what you should do is leave a sizeable force holding Munster and take eighty lords’ sons with you to marry the woman.”

And this was the counsel they decided on, and as Ceallachán was travelling on this journey, the night before he reached Áth Cliath, Mor, daughter of Aodh, son of Eochaidh, daughter of the king of Inis Fionnghall, who was Sitric’s wife, asked why he was making a match with Ceallachán after he had felled so many Norse nobles? “Not for his benefit did I press the match,” he said, “but with a view to practising treachery against him.”

The woman started at these words, since she’d secretly long been in love with Ceallachán since the time she saw him at Port Lairge; and she rose early the next morning and went in secret along the route she thought Ceallachán was coming; and when Ceallachán reached the spot she took him aside and revealed to him the plot that was being prepared by Sitric regarding him and his death; and when Ceallachán thought of returning he could not because the fields on either side of the road were full of bands of Norsemen lying in wait to capture him. As he tried to turn back they sprang on him from every side and killed a group of nobles that were with him, and some of the Norsemen were killed along with them. However, the bulk of the host set upon Ceallachán and he was captured, himself and Donn Cuan, son of Cinnéide, and they were taken as prisoners to Áth Cliath, and from there to Ard Macha, where there were held by nine Norse earls and their companies.

Regarding the band of Munster nobles who escaped this conflict, they travelled to Munster and told the news to Cinnéide and thereupon Cinnéide prepared two hosts to seek out Ceallachán, that is, a land force and a sea force; and he made Donnchadh, son of Caomh, king of the two Fearmaighs, leader of the land force, and Cinnéide began encouraging him, declaring that eleven of his ancestors were kings of Munster, being Airtre, Cathal son of Fionghaine, Fionghaine son of Cathal, Cú gan Mháthair [Motherless Hound], Cathal who was called Ceann Géagáin, Aodh, Flann Cathrach, Cairbre, Criomhthann, Eochaidh and Aonghus son of Natfraoch. Cinnéide also sent ten hundred Dál gCais with him with three leaders over them, namely Coscrach, Longargán and Conghalach, as the poem says: Let twenty hundred go northwards.

Here is the stanza of this poem quoting the words of Cinnéide:

Let Coscrach of the battles go there,

And lovable Longargán,

Let Conghalach from the lake go;

My three brothers I mean.

In addition, Cinnéide sent five hundred more of the Dál gCais with Síoda, son of Síoda of the clann Cuilein, and five hundred more of the Dál gCais with Deaghaidh, son of Domhnall, besides the fighting men that went from other free-born tribes of Munster. The second great force he sent to sea with Failbh Fionn, king of Desmond, as their leader.

As to the land force, they journeyed out of Munster into Connacht and sent skirmishers to Muaidh and to Iorrus and to Umhall to bring cattle to the Munster camp; and not long were the Munster camp waiting for the skirmishers when they saw a well-ordered host coming towards them, and their number was ten hundred with a single warrior in the lead; and as they reached the place Donnchadh, son of Caomh, asked who that company was. “A body of Munstermen,” he said, “namely, the Gaileanga and Luighne of the clann of Tadhg son of Cian, son of Oilill Ólum, and the men of Dealbhna, of the race of Dealbhaoth, son of Cas, son of Conall Eachluaith, who are giving you the strength of their arm in brotherly sympathy in opposing the Danes and rescuing Ceallachán, king of Munster, from them. And there are three valiant leaders at the head of that host, namely Aodh, son of Dualghus, with all the Gaileanga under him, Diamaid, son of Fionnacht, with the Luighnigh under him, and Donnchadh, son of Maoldomhnach, at the head of the men of Dealbhna.” And as a testimony of this is the historical poem that begins with this stanza:

The clann of Cian are there,

And Dealbhaoth all together,

Coming to the call,

And for you they will smite.

And here is how this host was. Five hundrend of them with shield and sword and five hundred were archers. The host of Munster and the company that had come to help them travelled from there to Tír Chonaill and they plundered the country. Muircheartach, son of Arnalaidh, came asking for restitution for the plunder with good will from Donnchadh, son of Caomh; and Donnchadh said they would only give him what remained of the plunder after the hosts had been satisfied. At this Muircheartach left the host and secretly sent messengers to the sons of Turgesius at Ard Macha informing them that the Munster host was seeking Ceallachán and his rescue.

As for the sons of Turgesius, they set out from Ard Mach, nine earls with their Norse host, and Ceallachán and Donn Cuan their prisoners. As for the Munster host, they journeyed to Ard Macha and killed all the Norsemen that came in their way and when they heard on the next day that Sitric and his host had gone with Ceallachán to Dún Dealgan they went in pursuit of them, and when Sitric perceived them coming close to the town, he himself and his host borded his ships and Ceallachán and Donn Cuan with them, and the Munster host came to the edge of the strand facing them and held parley with the Norsemen. And thereupon they saw a large fleet coming into the harbour towards them, and the Munstermen recognized that it was Failbhe Fionn and his fleet.

Failbhe and his fleet proceeded directly to meet the Norsemen and attacked the ship on which were Sitric and Tor and Maghnus, and he leapt on board Sitric’s ship, a sword in either hand; and he set to cutting the ropes with which Ceallachán was tied to the mast with the sword in his left hand until he freed Ceallachán and let him down on the ship’s deck; and then he gave Ceallachán the sword from his left hand. Ceallachán went from Sitric’s ship to Failbhe’s ship; and Failbhe continued to pound Norsemen until he was killed by the greater numbers of Norsemen and they cut off his head. Fianghal, leader to his people, took his place in the conflict, and seized Sitric forcefully by the breast, and threw them both overboard, so that they went to the bottom, so thus were they drowned.

Séaghdha and Conall, two other leaders, came and seized Sitric’s two brothers, i.e. Tor and Maghnus and threw them overboard so that all four were drowned. And similarly with every other company of the Gaels, they leapt on the Norsemen, until they were broken and separated, slain and thrown into disorder, so that there only escaped from them a small number through the swiftness of their ships; and they went ashore with Ceallachán who had thus been rescued from Norse bondage by the bravery and strength of the Munstermen; and they travelled on from there to Munster with Ceallachán, so that he took control of his country again.

And as they were leaving Áth Cliath for Munster Murchadh son of Flann, king of Leinster, thought to give them battle for the killing of Norsemen in rescuing Ceallachán from them. However, when they saw the bravery and strength of the Munstermen, they allowed them to pass without giving them battle.

⁜ Internet Archive: Foras Feasa ar Éirinn · The History of Ireland, Irish Texts Society 1908, pg. 223

⁜ CELT: Foras Feasa ar Éirinn (Book I-II)

⁜ Irish Script On Screen: UCD Franciscan Library MS A 14, f. 69 r. onwards

- Details

- Written by: Seán Ó Séaghdha

- Hits: 5236

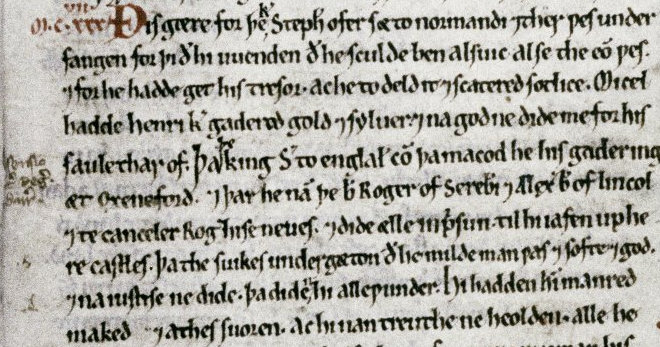

m·c·xxxvii·Ðis gære for þe king Stephne ofer sæ to normandi ⁊ther ƿes underfangen, forþi ðat hi ƿenden ðat he sculde ben alsuic alse the eom ƿes, ⁊ for he hadde get his treſor· ac he todeld it ⁊ scatered sotlice. Micel hadde Henri king gadered gold ⁊ syluer, ⁊ na god ne dide me for his saule tharof. Þa þe king Stephne to Englaland com, þa macod he his gadering æt Oxeneford. ⁊ þar he nam þe biscop Roger of Serebyri ⁊ Alexander biscop of Lincol ⁊ te canceler Roger hise neues, ⁊ dide ælle in prisun til hi iafen up here castles. Þa the suikes undergæton ðat he milde man ƿas ⁊ softe ⁊ god, ⁊ na iustise ne dide, þa diden hi alle ƿunder. Hi hadden him manred maked ⁊ athes suoren, ac hi nan treuthe ne heolden. Alle he ƿæron forsƿoren ⁊ here treothes forloren, for æuric rice man his castles makede ⁊ agænes him heolden. ⁊ fylden þe land ful of castles. Hi suencten suyðe þe uurecce men of þe land mid castelƿeorces. þa þe castles uuaren maked, þa fylden hi mid deoules ⁊ yuele men. Þa namen hi þa men þe hi ƿenden ðat ani god hefden, bathe be nihtes ⁊ be dæies, carlmen ⁊ ƿimmen, ⁊ diden heom in prisun ⁊ pined heom efter gold ⁊ syluer untellendlice pining· for ne uuæren næure nan martyrs sƿa pined alse hi ƿæron. Me henged up bi the fet ⁊ smoked heom mid ful smoke. Me henged bi the þumbes other bi the hefed ⁊ hengen bryniges on her fet. Me dide cnotted strenges abuton here hæued ⁊ uurythen it ðat it gæde to þe hærnes. Hi diden heom in quarterne þar nadres ⁊ snakes ⁊ pades ƿæron inne, ⁊ drapen heom sƿa. Sume hi diden in crucethus ðat is in an cæste þat ƿas scort ⁊ nareu ⁊ undep· ⁊ dide scærpe stanes þærinne· ⁊ þrengde þe man þærinne ðat him bræcon alle þe limes. In mani of þe castles ƿæron lof ⁊ grin· ðat ƿæron rachenteges ðat tƿa oþer thre men hadden onoh to bæron onne· þat ƿas sua maced· ðat is fæstned to an beom· ⁊ diden an scærp iren abuton þa mannes throte ⁊ his hals· ðat he ne myhte noƿiderƿardes· ne sitten ne lien ne slepen· oc bæron al ðat iren. Mani þusen hi drapen mid hungær. I ne can ne i ne mai tellen alle þe ƿunder ne alle þe pines ðat hi diden ƿrecce men on þis land· ⁊ ðat lastede þa ·xix· ƿintre ƿile Stephne ƿas king ⁊ æure it ƿas uuerse ⁊ uuerse. Hi læiden gæildes on the tunes æure um ƿile ⁊ clepeden it tenserie. Þa þe uurecce men ne hadden nammore to gyuen· þa ræueden hi ⁊ brendon alle the tunes· ðat ƿel þu myhtes faren al a dæis fare sculdest thu neure finden man in tune sittende· ne land tiled. Þa ƿas corn dære, ⁊ fle[s]c ⁊ cæse ⁊ butere· for nan ne ƿæs o þe land. Ƿrecce men sturuen of hungær. Sume ieden on ælmes þe ƿaren sum ƿile rice men. Sume flugen ut of lande. Ƿes næure gæt mare ƿreccehed on land ne næure hethen men ƿerse ne diden þan hi diden· for ouer sithon ne forbaren hi nouther circe ne cyrceiærd· oc namen al þe god ðat þarinne ƿas ⁊ brenden sythen þe cyrce ⁊ al tegædere. Ne hi ne forbaren biscopes land ne abbotes ne preostes· ac ræueden munekes ⁊ clerekes· ⁊ æuric man other þe ouermyhte. Gif tƿa men oþer ·iii· coman ridend to an tun· al þe tunscipe flugæn for heom· ƿenden ðat hi ƿæron ræueres. Þe biscopes ⁊ lered men heom cursede æure· oc ƿas heom naht þarof· for hi uueron al forcursæd ⁊ forsuoren ⁊ forloren. Ƿar sæ me tilede· þe erthe ne bar nan corn· for þe land ƿas al fordon mid suilce dædes. ⁊ hi sæden openlice ðat Crist slep· ⁊ his halechen. Suilc ⁊ mare þanne ƿe cunnen sæin· ƿe þolenden ·xix· ƿintre for ure sinnes.

⁜ englesaxe Early Middle-English Texts: The Peterborough Chronicle 1137

⁜ Bodleian Library, Oxford: MS. Laud Misc. 636, fol. 089r (‘The Peterborough Chronicle’, E text)

1137·This year the king Stephen went across the sea to Normandy, and was received there because they imagined that he would be just like the uncle was, and because he still had his treasury; but he distributed and scattered it stupidly. King Henry had gathered gold and silver and no good was done for his soul thereby. When the king Stephen came to England he held his council at Oxford, and there he seized the bishop Roger of Salisbury and his nephews, Alexander bishop of Lincoln and the chancellor Roger ⁜ , and put all in prison until they gave up their castles. Then when the traitors realised that Stephen was a mild man, gentle and good, and imposed no penalty, they committed every enormity. They had done him homage and sworn oaths, but they held to no pledge. They were all forsworn and their pledges lost because every powerful man made his castles and held them against him, and filled the land full of castles. They greatly oppressed the wretched men of the land with castle-work; then when the castles were made, they filled them with devils and evil men. Then both by night and by day they seized those men whom they imagined had any wealth, common men and women, and put them in prison to get their gold and silver, and tortured them with unspeakable tortures, for no martyrs were ever tortured as they were. They hung them up by the feet and smoked them with foul smoke. They hung them by the thumbs, or by the head, and hung mail-coats on their feet. They put knotted strings round their heads and twisted till it went to the brains. They put them in dungeons where there were adders and snakes and toads, and destroyed them thus. Some they put into a ‘crucet-hus’, that is, into a chest that was short and narrow and shallow, and put sharp stones in there and crushed the man in there, so that he had all the limbs broken. In many of the castles was a ‘lof and grin’, that were chains such that two or three men had enough to do to carry one. It was made thus: it is fastened to a beam, and a sharp iron put around the man's throat and his neck so that he could not move in any direction, neither sit nor lie nor sleep, but carry all that iron. Many thousands they destroyed with hunger. I do not know nor can I tell all the horrors nor all the tortures that they did to wretched men in this land. And it lasted the 19 years while Stephen was king, and it always grew worse and worse. They laid a tax upon the villages time and again, and called it tenserie. Then when the wretched men had no more to give, they robbed and burned all the villages, so that you could well go a whole day’s journey and never find anyone occupying a village or land tilled. Then corn was dear, and flesh and cheese and butter, because there was none in the land. Wretched men starved with hunger; some who were once powerful men went on alms; some fled out of the land. Never before was there more wretchedness in the land, nor ever did heathen men worse than they did. Too many times they spared neither church nor churchyard, but took everything of value that was in it, and afterwards burned the church and everything together. They did not spare the land of bishops nor of abbots nor of priests, but robbed monks and clerks; and every man overpowered the other. If two or three men came riding to a village, all the villagers fled because of them, imagining that they were robbers. The bishops and the clergy always cursed them but that was nothing to them, because they were all accursed and forsworn and lost. Wherever men tilled, the earth bore no corn because the land was all done for with such deeds; and they said openly that Christ and His saints slept. Such things, and more than we know how to tell, we suffered 19 years for our sins.

⁜ Yale, Viking Sources in Translation: Anglo-Saxon Chronicle: Peterborough MS

- Details

- Written by: Seán Ó Séaghdha

- Hits: 3601

- Details

- Written by: Seán Ó Séaghdha

- Hits: 1836

- Details

- Written by: Seán Ó Séaghdha

- Hits: 886

(Bad?) Translation of the Dedication from the first edition of Savinien de Cyrano de Bergerac’s Histoire comique…contenant les Estats & Empires de la Lune.

TO MILORD

TANNEGVY

RENAVLT DES

BOISCLAIRS;

Knight , Aduiſor

to the King in his Coun-

cils, & Grand Pre-

uoſt of Bourgogne &

Breſſe.

SIR,

I fulfill the laſt wiſh of a dying man whom you obliged with noteworthy benifience during his life. Since he was known to an infinitude of people of intelligence, by the fine fire of his own, it was abſolutely vnbearable, that many perſons knew not the diſgrace that a dangerous injury followed by a violent feuer, cauſed him ſome months before his death. Many knew not by what good Spirit he had been ſaued, but he belieued that the name ſhould not be leſs public, than the aduantage he deriued therefrom. You were his Friend, you often auowed it, & you euen gaue euidence of it on many occaſions, when you deuined his needs ; but what was this act, that other Men did not act as you did ? how did this appear to our Friend, compared to your appearance to a hundred others who were not of his ſtamp ? He muſt have ſtood out from the crowd, & that your generoſity diſtinguiſhed him from the great number that you have obliged, ſhowed not only, as Ariſtotle ſaid, Generoſum eſt quod à natura non degenerat

Ariſt. Hiſt. anim. op. primo. that it had not degenerated, but had enriched of itſelf in ſupport of ſo worthy a ſubject. So that when you had the goodneſs to giue him proofs of your protection & your friendſhip in his illneſs, whoſe courſe you arreſted by your care & the generous aſsiſtances you gave him in the extremity of his moſt violent euils ; it was ſuch a powerful protection for him , that he once more hoped from you that which a little before his death he begged me to aſk of you for this work; & that will alſo be of that great truſt , & of that laſt wiſh that you will recognize as thoſe which he ought to have had from your friendſhip ; ſince it is in that fatal moment that the mouth ſpeaks like the heart.

Lucret.

lib. 3.Nam veræ voces tum demum pectore ab imo eliciuntur.

And I haue made myſelf the Interpeter of his own that much more willingly, ſince I took equal part in his diſgrace, as in the good that was known to him ; & for that reaſon, as by my own inclination , I am truly,

SIR,

Your moſt humble, & very

affectionate ſeruant.

Le Bret.

- Details

- Written by: Seán Ó Séaghdha

- Hits: 1453

Dedication from the first edition of Savinien de Cyrano de Bergerac’s Histoire comique…contenant les Estats & Empires de la Lune.

A MESSIRE

TANNEGVY

RENAVLT DES

BOISCLAIRS;

Cheualier , Conſeiller

du Roy en ſes Con-

ſeils, & Grand Pre-

uoſt de Bourgogne &

Breſſe.

MONSIEVR,

Ie ſatisfaits à la derniere volonté d’vn mort que vous obligeaſtes d’vn ſignalé bienfait pendant ſa vie. Comme il eſtoit connu d’vne infinité de gens d’eſprit, par le beau feu du ſien, il fut abſolument imposſſible , que beaucoup de perſõnes ne ſceuſſent la diſgrace qu’vne dangereuſe bleſſure ſuiuie d’vne violente fiévre, luy cauſa quelques mois deuant ſa mort. Pluſieurs ont ignoré par quel bon Démon il y auoit eſté ſecouru , mais il a crû que le nom n’en deuoit pas eſtre moins public, que l’action luy en fut aduantageuſe. Vous eſtiez ſon Amy, vous l’en aviez ſouuent aſſeuré , & meſme vous le luy auiez témoigné en pluſieurs rencontres, où vous ſçauiez le beſoin qu’il en auoit ; mais qu’eſtoit - ce faire, que quelques autres Hommes n’euſſent fait comme vous ? qu’eſtoit - ce paroiſtre enuers noſtre Amy , que ce que vous paroiſſiez enuers cent autres qui n’eſtoient point de ſa trempe ? Il falloit donc le tirer de la preſſe, & que voſtre generoſité le diſtinguant du grand nombre de ceux que vous obligiez, fiſt voir non ſeulement, comme parle Ariſtote, Generoſum eſt quod à natura non degenerat

Ariſt. Hiſt. anim. op. primo.qu’elle n’auoit pas dégeneré , mais qu’elle auoit enchery ſur ſoy-meſme en faueur d’vn ſi digne ſujet. De ſorte que quand vous euſtes la bonté de luy rendre des preuues de voſtre protection & de voſtre amitié dans ſa maladie, dont vous arreſtâtes le cours par vos ſoins & les aſſiſtances genereuſes que vous luy rendiſtes en l’extremité de ſes maux les plus violens ; ce fut d’vne ſi puiſſante protection pour luy , qui’il eſpera de vous encore celle qu’vn peu deuant ſa mort il me pria de vous demander pour cet ouurage; & ce ſera auſſi de cette grande confiance , & de ce dernier ſentimẽt que vous iugerez de ceux qu’il doit auoir eus de voſtre amitié ; puis que c’eſt dans ce moment fatal que la bouche parle comme le cœur.

Lucret.

lib. 3.Nam veræ voces tum demum pectore ab imo eliciuntur.

Et ie me ſuis rendu l’Interprete du ſien d’autant plus volontiers, que ie prenois part également à ſes diſgraces, comme au bien qu’on luy ſaiſoit ; & que par cette raiſon, comme par mon inclination particuliere , ie ſuis en verité,

MONSIEVR,

Voſtre tres-humble, & tres-

affectionné ſeruiteur.

Le Bret.

- Jumeaux?

- Carry On Up The Neander

- Daylight Saving Ugliness

- Le chat ministériel

- Mot du jour: limoger

- Unfortunate angle?

- Romanians are still revolting

- Greasy poll

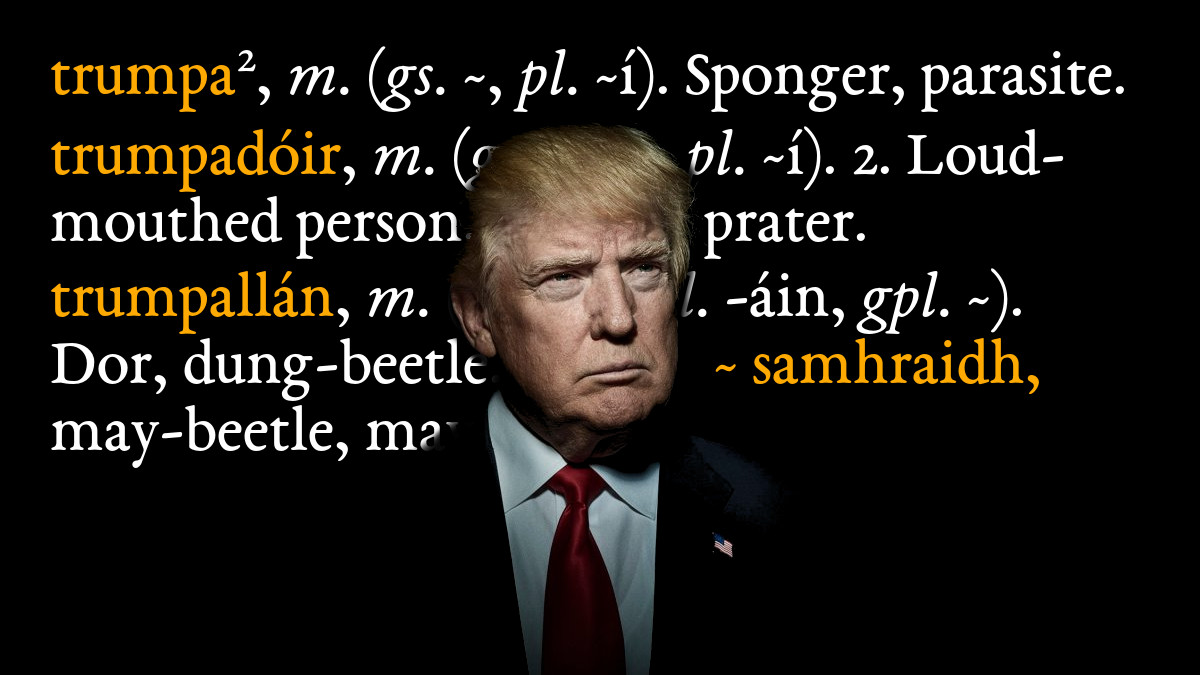

- Trumpf

- Will Fillon be France’s Thatcher?

- “Homophobes” slanderous?

- The Colour Purple

- Politics in the Giro

- La ville lumière

- Giroration

- The picture Peter tried to suppress